It’s whatever people have in their heads and hearts that directs them to where they go. – Linda Dawe

Linda is someone I have had the pleasure of knowing in one way or another for almost two decades. I had the opportunity to get to know Linda through her daughter, Tiffany, who is my age, so I always enjoy talking to her in historical context because I can kind of relate to timelines from the perspective of how old Tiffany and I would have been, and also to Linda being part of my parents’ generation.

Linda has some great stories that I’ve had the chance to hear and recently, she was offering her stories as material for something else I’ve been working on. It kind of hit me how much there has been a thread weaving through her life of this sort of wondering, learning and “moving toward.” I realized as she spoke about her early wondering about class, race, religion and abilities, that she has been curious and working through ideas for many years. It all fit so well with my own curiosity about self-directed learning in people of all ages and stages.

Linda was very humble when I suggested this, but I think we don’t always see the interesting pieces in ourselves that others see in us.

So, here is a transcript of our conversation …

Erin: Linda, as you know, I’ve really appreciated you sharing so many great tidbits and, in some cases, full stories about your childhood. Of course, I’ve had the opportunity over the years to hear you tell more current stories, and have always noticed what a true lifelong learner you are. It was neat to recently step back into some of your earlier experiences and unexpectedly notice a few things that seemed to really reflect the kind of learning and work you still do today.

Could you just give a brief snapshot of where you grew up and in what era? A little bit about your family as well?

Linda: Well, I grew up in Springhill, Nova Scotia and I was born in 1943, which tells my age. I basically lived there until I was 19 years old and very seldom left Springhill, except for maybe a few surrounding towns. The first couple of years, I lived with my parents and then we moved into my grandparents’ house and at that time, there was myself, my sister, my parents, my grandparents, my aunt and my great grandfather, so we all lived together in one rather big house. I had other family in Springhill, at least three other sets of family – cousins and aunts and uncles. It was a small town and in some ways, a closely knit town and in other ways, probably not, but it was a place where people were very much linked, just by virtue of what was happening in the town in terms of, I guess, commerce or industry.

Erin: Okay, and it was a coal mining town, Linda?

Linda: Yes, it was a coal mining town. It had quite extensive coal fields and in fact, one of our coal mines was the deepest coal mine in North America. It was about two miles deep. That would have been the coal mine that my father, my grandfather, my great grandfather and some of my uncles would have worked in over the years.

Erin: Oh wow.

Linda: Yes, and it was a town that had a very sad history in the 1950s of experiencing mining disasters, which were very, very devastating, not only to the people, but also to the town itself in terms of how people would make a living.

I remember growing up, before I had actually experienced mining disasters (although there were many mining accidents. It wasn’t unusual in a week to have at least someone who lost their life in a mine), what I mainly heard about was the mining disaster that happened in, I think it was, 1891, and it was a different site from where my father worked, but, yeah, it was a huge disaster. I think there were about 125 men and boys who died. It was in the middle of winter and I remember that being talked about and referred to fairly frequently. It was a story that stood out because of its severity, but it was also interesting in that there weren’t a lot of stories shared in great detail of years past. There were snippets of stories about the war and being short of food and just little bits of stories, but that was a story that was relayed almost, I think, in its entirety on fairly frequent occasions.

Erin: Wow. So, I didn’t know that part, Linda. I knew there had been a couple of major disasters, but the idea that it wasn’t unusual for a miner to die here and there, outside of disasters – that really seems like a lot for a town to deal with.

Do you think that growing up in a town that – well, a real “working” town, where people had to be pretty resourceful – that you’d have to be quite hardy? I mean even emotionally, I think, you’d have to be pretty hardy to have family members going into the mines every day. Do you think that impacted a part of you in any way as far as certain strengths or a certain work ethic or sense of resourcefulness?

Linda: I think what it left me with, if I just think of it in terms of myself, was that you understood that part of what life meant was that you had to work hard. That was kind of reinforced in my parents with them being very determined that their children were going to have a decent education. So, it wasn’t the idea that you were going to go off to university and get your Ph.D or anything like that, but you were going to do better than they did. I think that’s a common aspiration that parents often have for their children. My mother probably went to school until Grade 7 and my father until Grade 8. There was never any question about whether you did your homework or not. You just did your homework and you did as well as you could do because the understanding at that time was that it meant that you were going to have a better life. I think that was an expectation that maybe all parents had, but I always felt, from my parents, that it was vital, because it meant that you probably wouldn’t be subject to, I don’t know … the bad things in life or the level of anxiety that you might have because of the dangers of whatever work was available, especially the men. Women didn’t work in the mines. Life working in a mine depended on how well the mines were working and whether or not there were strikes would determine what you could depend on financially. I think the idea of an education was that it would diminish a lot of that and be more secure, and maybe just easier.

Erin: Okay, yes, that makes a lot of sense – thank you. When we were talking recently, I noticed the awareness here and there you had about people and circumstances. It just kind of naturally came up in our conversation. People of different races was one of the things I remember you wondering about. Black people have a very rich history in Nova Scotia. Could you describe a bit about the racial context in your area of Nova Scotia at the time, at least as far as how you perceived it as a child? Not so much your exact feelings about it, because I think we’ll get to that, but what your best guess is as to how black people and white people lived together (or not) in the way you experienced it growing up.

Linda: I had no real awareness of black people as a very young child. There was no actual talk of different races, except, perhaps for the mention of a man named Bob Sylvie. Bob Sylvie had a wonderful singing voice that my father and many of the people in the town admired. I maybe remember hearing of an event and Bob Sylvie would sing. Even though I now know there were black people in the area, I never saw or interacted with any at a really young age.

I became aware of people of colour when I was maybe seven or eight years old – I have the picture in my mind. There were alleyways from one street to another in the area where I lived and I can remember being in front of the neighbour’s house across the street and three women of colour – I think they were young women – were walking through and they were crossing the streets through the alleys and one woman was a very, tall woman. She seemed severe-looking to me because she wasn’t smiling and my reaction was to be wary. I don’t remember ever hearing anything that suggested that to me, but I had a sense – there was something in my head that either I was to be wary of them or that this was really a very unusual thing.

And it wasn’t unusual for people to come up through the alleyways because that’s kind of how we went back and forth from one street to the other, but I had never seen the women before. I had never seen them in town or any place else like in church or in school. That image is very, very clear in my mind and I can’t exactly say the feeling – whether I was wary or surprised or whatever. As time went on, nothing really changed as far as my knowledge of people of colour in the town. I continued on through elementary school and other things in my childhood and didn’t meet up with any other black people until I went to high school and that was my first experience of having a black person in the classroom with me. There was … there was just, you know, I wondered about the three young women of colour I had seen and I think there were probably certain kinds of conversation and words spoken about black people that caused me to wonder but I don’t know what those were.

Erin: You kind of had that feeling that some seeds had been planted but you can’t remember exactly when or what.

Linda: Yes.

Erin: So Linda, my curiosity is that you’re seeing these women in town and you’ve spoken of Bob Sylvie … people of colour must have needed stores and businesses and so on. Was there another nearby town or nearby community somehow that was settled in the area that was operating separately somehow? I mean if you were in high school with a few people and the women likely have families, there must have been a community in close proximity, but a separate community?

Linda: Yes, people lived within the town boundaries, I came to realize. In my mind, the town was almost like a semi-circle, so when I was very little – the first couple of years of my life, we lived on a road, It was an ordinary road and part of it was really quite well to do, but not our house … I know now that beyond that, sort of around the perimeter of that area of town, was where many people of colour lived. It kind of extended up to the hills. We lived in a sort of flat part of town and then every street had a hill going up. I’m guessing that much like there were in Africville and Halifax, I imagine there were stores and churches and there was a school out that way. I imagine that’s where the children would have gone to school and people would have had their own church and stores. I do remember one store that had a soda fountain, but I don’t have a memory of much else in that store.

Erin: Interesting. It sounds like you were aware of your own church, your own school and stores and you were kind of aware that something more was there, but when you’re a kid, it’s maybe not as relevant to you.

Linda: Yeah, yeah. There were no black children in school with me until I got to high school and there was only one high school, so once you got to high school, that’s where everybody went, but even in high school, there weren’t many black students there.

However, I do realize now that there would have been men of colour working in the mines, alongside my father and relatives. There was a miner, Maurice Ruddick, who became very famous after a mining disaster in 1958 so I heard about quite a lot about that. He was rescued from the mine after 9 days. He was a singer and apparently sang songs while everyone was trapped and was credited with keeping other miners alive. He also wrote a poem while he was trapped, which had quite an impact. I don’t know how many people realized it but I believe it inspired many songs. I remember my sister singing one of them. He and some of his daughters formed a musical group, the Singing Miner and the Minerettes, and travelled around performing.

He was awarded Canadian Citizen of the Year, and he and his fellow survivors were invited by the Governor of Georgia to go down and stay at a resort. When the governor found out he was black, he said that he and his family would need to stay in a trailer on the property and only go to segregated places while the other miners stayed in the resort. When they found this out, the other miners said that they would not go if Maurice had to stay in a separate place, but Maurice insisted that he was going anyway and would stay in the trailer – he wanted them to have the opportunity. He also felt that it might be a chance to open some people’s eyes.

What’s interesting though is that it all kind of faded away and didn’t endure. He was respected because he had done something heroic, but there wasn’t much recognition for black people apart from that kind of thing, it seemed.

Erin: That is very, very interesting. I hadn’t realized all of that. That’s quite a story and quite an illustration of the way things were thought about – wow. Linda, so you saw the young women in town and you’d heard about Bob Sylvie and then you met a few black students in your high school. Did you ever wonder out loud about it or ask any questions? Or was it just kind of the way it was?

Linda: Umm, I don’t remember asking direct questions. I remember wondering. I wondered about those three young women. I always wondered about them and I imagine they may have been on their way up to the hospital and that they maybe were going up to the hospital that way because they didn’t feel they could go through the downtown? I wondered if they didn’t feel welcome to go through the downtown or safe? I wondered if they didn’t think it belonged to them. I don’t know but I just remember having these thoughts – not continuously – but on and off, these thoughts were in my head.

There was a little bit of a connection, I think, to the fact that we were Catholic and it was basically a Protestant town. I don’t know how much being Catholic was an issue for Protestants, but being Catholic, the way I was brought up anyway, you just didn’t go to a Protestant church. It just was not allowed. So, I wondered about that … I could never quite figure that out either.

Erin: So, you were noticing a division there as well.

Linda: Yes.

Erin: Linda, something that I noticed when you were sharing your stories with me recently was that you spoke of people, whether it was family or neighbours or whoever, in really individual ways. You noticed details about people – their personalities, gifts, interests, etc – I kind of felt like I could get a sense of each person as you described them. We’ve already talked about the racial piece, and I also noticed you mention socioeconomic and religious details as well. I guess what I began to hear in you, is the early stages of the person I know now. So, that is someone who has spent a big portion of their adult life noticing and questioning and working toward the idea that life is better and community is stronger when everyone has a chance to be part of it.

I think that your experience as a mother has had a lot to do with that because as mothers we need to learn and grow and work toward new things for our kids but I’ve seen you work beyond what you needed to do, taking time to share your experience with other families, and maybe just also learning more as part of natural curiosity.

So, I’ve kind of jumped ahead, but just to come back to your experience as a mother and how that led to imagining and learning and needing to work toward things – could you talk about that?

Linda: My goodness, you know, what you think and what you feel years back, sometimes when you start thinking about that again, you don’t know yourself why you thought and felt that way and the reasoning. Well, everything is so connected …my thoughts and feelings around how I reacted and responded to everything around the time that Tiffany was diagnosed with a disability, and that wasn’t until she was about eleven months old. Prior to that, I didn’t realize that she had a disability, but I was realizing that she was behind in her development, but it again kind of circles back to my experiences as a child, with people with disabilities -two young girls in my town who had Down Syndrome and my cousin, who had been placed in an institution as a young child.

Later on, after Tiffany was born, and after she had a diagnosis, my uncle told me a story about, I believe, my great grandparents having a child with a disability. They ended up having eight children, and at some point, that child was placed in an institution and died. She was buried in the local cemetery and I had never heard of her. My uncle, who was essentially the holder of the family information, told me the story. Her name was Anastasia and I can remember when I heard that story, I was surprised, maybe even shocked because I hadn’t known anything about her. I can remember thinking that maybe I would have called Tiffany “Anastasia” – not because of having a disability because I wouldn’t even have known that about Tiffany at the time of naming her, but because to me, that was a very lonely story. I kept thinking about my cousin Marilyn, who lived in an institution, and Anastasia. I remember meeting Marilyn many years ago, when I was in my teens, just very, very briefly. My sisters and I visited the institution to perform music as entertainment there and it just seemed very, very lonely. That’s the feeling I had, or aloneness or something like that. So, I did wonder a lot about my cousin Marilyn, but I also, after hearing the story about Anastasia, I just tried to understand that. Not the fact that she was she was placed in an institution, because that’s what happened at that time, but that I had never heard anything really about her in thirty years.

In our town, there were two young girls with Down Syndrome and they both went to school. One was sent to school with no kind of plan in mind. She just went to school and wandered around the school from one place to another and I noticed that nobody seemed to pay much attention to her. Sometimes she would be crying. She seemed very dishevelled and what not. The other girl was the daughter of a school teacher and we were friends with the other daughters and I only saw her a couple of times because her school would have been different from my school. I just remember her being beautiful. She was well-dressed and her mother brought her to school every day. Her mother taught in the same school where she went. I used to wonder why, through my young eyes, those girls were the same – like they both had physical disabilities – but why they were so different in sort of the way they presented or the way people saw them. I wondered why that was. I started to think it was maybe socioeconomic (not in those words at the age I was), and that the one family where the parents were teachers had more resources, and maybe the school had more resources than the other girl whose family were labourers.

When I was very, very little, I was walking down the road with my mother to visit my grandparents and we passed a house. It was a brown house and there was girl on the porch who would have been older than I was. She had red hair and it was blowing all over the place. I noticed that she had a rope tied around her waist. She wasn’t tied up tightly, but it was sort of a harness and she was waving her arms all around. I said to my mother, “Who’s that?” and my mother said, “Shhh!” So I knew not to ask too much about it, but she must have had a disability. The main thing I noticed was how dishevelled her hair was and I was wondering, “Isn’t somebody going to comb her hair?” I had curls as a child and my mother really worked hard at always combing my hair nicely, so that was the main thing in my mind when I saw this girl, was wondering why somebody wouldn’t have been combing her hair. That stayed in my mind for a long, long time.

The other thing I remembered was that when I was living in Ottawa, I used to travel back and forth to the hospital on the bus and I can remember one day, two young men got on the bus and they both had Down Syndrome. I thought, “Wow, they can travel on the bus.” You know, it was like shock and realization all at the same time. I imagine they might have been coming from work or a workshop of some kind. It would have been about 4:00 in the afternoon and I just knew that that was right. I just knew that them getting on the bus and doing their thing was right. They could do that.

I was a nurse and I worked in labour and delivery and there were children who were born who had physical or developmental disabilities of one kind or the other. I sometimes thought, “What would I do? How would I react if I had a child with a disability?” I wondered whether it would make a difference whether it was a physical disability or a development disability. And in my mind, I thought, that it might be better if it were a developmental disability because then they maybe wouldn’t be as aware that they were different. I hadn’t really developed my thinking too much at that point!

Erin: Right, but interesting that you were noticing so much, I guess, differences between people, and maybe you were noticing those differences so much because of the way our society was set up, and especially at that time. I mean, certainly there are distinctions between people but you were operating with a certain frame of reference and essentially expanding it over time as you met people.

When you began to realize that Tiffany had a disability, maybe not so much when you began to wonder about it, but hearing it for sure and letting it sink in, do you think some of those earlier thoughts impacted you? Because some people wouldn’t have given those earlier observations much thought. Not everyone would have been noticing and wondering about those things. So, I guess I’m wondering what you thought it would mean for her life.

Linda: So, I found out for sure from a pediatric neurologist and until she was about six months old, I felt like her development was typical. I didn’t have any concerns about that and then one day, I was walking with her, I was walking along holding her under her arms, as you do with babies as they’re getting closer to what you might think of as walking age. I had done this many times and a number of days in a row. She just didn’t seem to have the same inclination to move her legs, so that was little bit of a sign or something in my head. She also wasn’t sitting up really. I had been to Nova Scotia with her when she was about six months old and was on the beach with her and my mother and we saw another baby. My mother knew a lot about babies and I asked her how old she thought the other baby was. She said, “Oh, maybe around 7 months old” and I just looked at her and she said, “Oh, maybe around 5 months old.” She just looked at me and there was some sadness in her eyes. Then really, nothing else was said.

A bit of time went by and I called my pediatrician, who I didn’t like at all. He was quite a rude and ignorant man, but anyway, I called him and said that Tiffany seemed to be behind in her development. He took an X-ray of her skull. He told me that perhaps there was something with her fontanelles. Then, I think it was around Easter weekend and he called me back and said that no, everything was fine. I asked him what that meant and he said that we would just wait and see. I had a tendency not to probe with him too much because he was quite disagreeable most of the time. Tiffany was eleven months old before she got to the pediatric neurologist. I was told that she had microcephaly and that children with microcephaly didn’t really survive that long. He thought she might have a life expectancy of about 6 years old.

So I was very, very, very upset. I was by myself in downtown Toronto. Her dad had driven us there before he went to work and I called him and I was just very upset. We went home and we were talking about it and I can remember him saying, ”I don’t think I can handle this.” I just said, “Well, the only other choice is an institution.” And so that was the last time that was talked about really. We went to visit his parents and they were dismayed, but supportive.

I couldn’t figure out why the doctor would say that she would only live to be six, because she was profoundly healthy. She had a great appetite, she was growing, she noticed lots of things around her. I just couldn’t figure that out. I was upset and very, very angry. I think that really what I most upset about was that he had said she was going to die, potentially by the time she was six.

I had a phone call with my mother. We called back and forth regularly and I didn’t call her. She called me and she said, “Hello, Linda. How are you, dear?” which is what she said every single time. Then she said, “How is Tiffany?” and I just burst into tears. She asked me what the matter was and I told her that Tiffany had gone to the doctor and he told us that she was mentally retarded, which is what the words were in those days. My mother wasn’t a person who talked a lot – she was kind of a woman of few words. She just said, “But why are you crying?” And I said well, “Because Tiffany is mentally retarded.” And she said, “But why are you crying?” And I said, “Because I’m afraid nobody will love her.” And she said, “Linda dear, that means that we will only love her more.”

Erin: Hmmm … wow.

Linda: And after that I was fine, really… I mean, I wasn’t fine as to whether the doctor was right about her not living very long, but I think it was at that point that I was just very determined that all the things that should happen for any child, should happen for Tiffany in some way or the other.

I can’t say that it didn’t bother me that she had a disability. I wished she didn’t, but it wasn’t a shameful thing and I didn’t think it was the worst thing could happen in my life or anything like that. I don’t remember feeling that way, but it was a common thing for people to ask where we were going to “put” her. I remember my husband’s aunt asking that and others as well and again, I guess my answer was that where I was going to put her was where she already was – her home.

Erin: Right.

Linda: After that, I think that I was just very, very, very lucky in terms of the connections I was able to make with people, the mindset that those people had and the guidance that I was given. Well, and the support … it was all very positive. I just happened to run into the right people. I didn’t really know much of what to do at that point. I guess I went back to my pediatrician … he had never indicated to me in any way, shape or form that there was anything amiss and we found out that it had actually been determined at birth that she had microcephaly. His response when I asked him about that was, “Well, I just wanted to give you a chance to come to love her.”

Erin: Oh!

Linda: I thought that was the most disgraceful thing I had ever heard in my whole life. It did fit in with the way he would have thought though, you know?

Erin: Yes, right, okay.

Linda : So I just said to him that I loved her before she was born, like most mothers do. Anyway, yeah, so again, I just connected with people that were very supportive, very kind, just very understanding in a sort of ordinary way that all children are worth investing in, giving their time to and figuring things out. I think it was also a timing thing because we were sort of on the cusp of moving from institutionalization into more community-based supports.

I met lots and lots of other families, some of whom had children who were in institutions. I didn’t understand everything that everyone was talking about. We were moving into the era of talking about SRV (Social Role Valorization) and some of it seemed very complex.

Most often what I do is that I hear something and I go away and think about it, and sometimes I have to go away and think about it quite a bit before I totally understand it or whatever, but there was so much of that that made sense, or if it didn’t make sense entirely, I felt compelled to just continue exploring that and learning more. There were pieces there in some of the philosophies being discussed that I didn’t agree with entirely, but I came to understand how I could use it as a foundation for moving forward. For moving forward with Tiffany’s life in a way she deserved, and moving forward in a way that the world would understand about people with disabilities.

So it was very much like the process that I went through as a child just in terms of wondering about religion and race and income class. You know I didn’t – I had those thoughts in my head and was wondering about the inequities across the board or whatever, but I didn’t do anything intentionally to figure that out. I didn’t really set out to learn and educate myself, but I think what I did was just keep my mind open. I didn’t delve into learning. I don’t have a tendency to delve into people’s lives anyway, so I was more interested in understanding than being specifically knowledgeable, if that makes any sense.

Erin: Yeah, yes, I think it does. You were curious maybe about the process or patterns rather the details?

Linda: Yeah. Overall, with all that’s happening right now, and questions about how people can understand what people of colour have gone through and what needs to change, I hear people saying that people have to ask questions, but as a child, I didn’t ask very many questions. It just wasn’t the thing to do back then. When I did ask questions, I almost always got into trouble, so I’m not inclined to learn that way. The idea of asking people about their experiences – I almost always feel as if I’m being nosy or intrusive.

Erin: Right. Right. So, it’s kind of like you’re observing and you’re listening and you kind of let that percolate and that understanding develops as it needs to.

Linda: Yeah, and everything is so connected because I know if people ask me about Tiffany and her disability, my back gets up. I guess it seems like these are questions being asked about somebody that you wouldn’t ask somebody else.

I think I learned to – well, when Tiffany was quite young, we had just moved. My mother came to visit and a neighbour came by and asked if she and another neighbour could come by to get to know each other. There was a white woman and a black woman and we had a nice couple of hours and after they left my mother turned to me and said, “Well, she was lovely.” So, she was the neighbour who was black. Yes. So, at that moment, my mother was learning something. I think that’s a lot of the way we often learn, if we are just kind of open to the things coming into us? Just seeing the things in life, not necessarily questioning people and gathering lots of facts and information, but more just relying on our experiences and what opportunities they bring.

Erin: Yeah, yeah. You know, just to draw back a bit, you were talking about how everything is connected, and maybe not being 100% on board with every aspect of a philosophy. I think with so many things, something can provide us with a set of principles – I think you used the word foundation – and we take the pieces that work best for us or that we understand in that moment without maybe understanding or agreeing with every single piece, and other pieces may not be relevant at that time or maybe ever for us, but I still think we can use the foundation. There may be those outlier pieces, where you go, “Oh, you know that doesn’t really fit for us, or I’m not 100% on that,” but the philosophy itself can still provide a foundation for learning and moving forward.

I wonder if the fact that you found that SRV/Values based foundation still really informed how you went forward. What I know of you is that it’s not about having all the right answers. You can correct me here, because I obviously don’t have all the right words, but you had a direction to move toward and you knew that Tiffany had as much right as anybody to have a really good life and, just as much as that, other people would be better for having Tiffany in regular life. So, yes, it’s partly about her rights and it’s also about the importance of her taking her place in the world.

That’s how it’s always seemed to me. It’s not that you have a fixed end, because you can’t, but those two pieces seem to be foundational.

Linda: Well, yeah, and when I go back to thinking about some of the people I’ve met over the years, some of the parents, and they have great disappointment in their child, and I don’t think this is very many parents, but also there might be a kind of reluctance to being open and just learning a little bit more. I think that might just help them see what might be possible, because according to medical people, there just wasn’t going to be much that was possible and I think it’s pretty obvious that Tiffany has contributed volumes to people’s lives over the course of her life, and continues to.

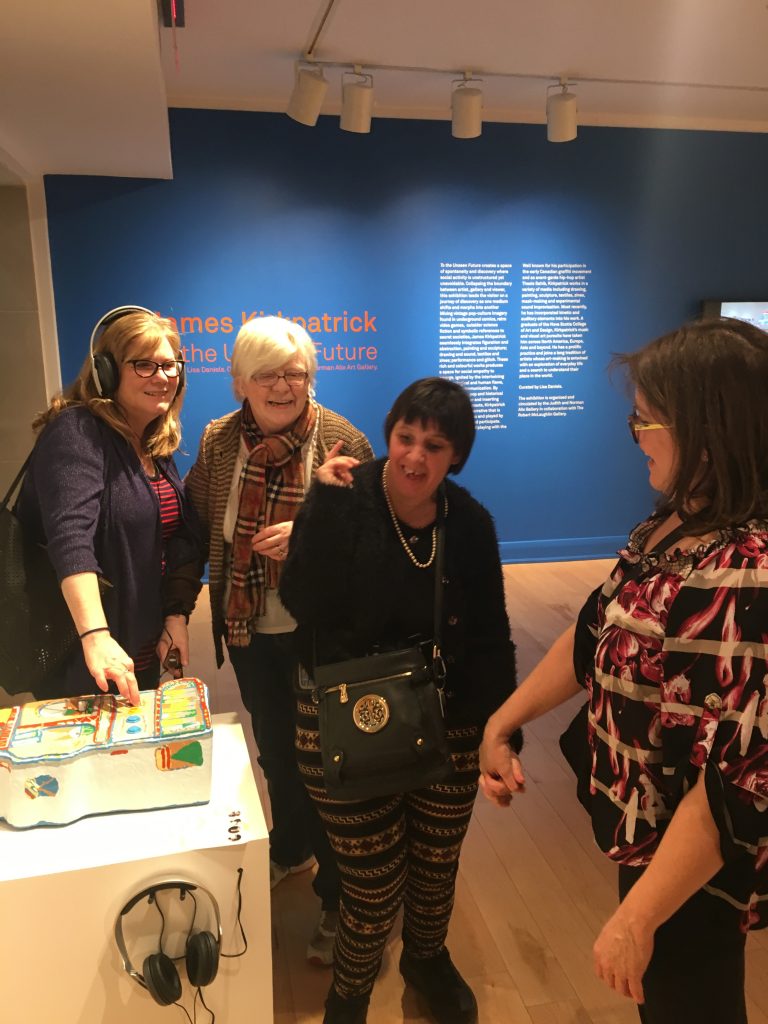

Linda, second from the left, enjoying an evening at the art gallery with Tiffany, second from the right, and friends.

Erin: Was there a point that you realized that this was going to be ongoing learning? That there was always more to figure out? Or did you always know that?

I ask this because I think that people often look for concrete answers or for the particular path that would work best for them, kind of like a box to check off, but once we begin learning things, it leads to the realization that there’s always more. If we’re developing an evolving vision for our life or in partnership with someone else, as you’re doing with Tiffany, there always seem to be new things emerging to figure out and to learn.

I guess specifically I’m thinking of all the work you connected with others to do around Tiffany having her own home and it must have been so much energy invested. Once that goal was met, it was really just another step toward the process – in some ways, it might have seemed like a new beginning. So, it’s kind of like, “yes, that goal is met, but hold on, there’s lots more to this vision and it will always be evolving, so let’s keep learning and working!”

Linda: Yes, I think I understood that there’s no end. Like there’s never a time when things are all figured out. It might feel that way today, but then tomorrow I realize that it’s not all figured out. I think Tiffany moving into her own place, to me, speaking just today, that’s a point of completion because it is her place, has been for over 25 years, and I can’t foresee at this point in time where it wouldn’t always be, but I also understand it may well be that it won’t be her place forever. That would be a real point of worry, because I won’t be here. As long as I’m here, it will be her place. That thought connects to the people – the different people she’s connected to and that’s part of having faith in people. So, if you think of Tiffany moving into her own place as being a forever solution, a real solution, that will then bring you to questions like: Who are the people? How is she going to be supported in her own place forever? And that brings you to the people and the connections and the figuring out, so it’s always more learning and figuring out. It’s complicated, but it’s sort of like anybody’s life in many ways, you know.

Erin: Yeah, Yeah. It reminds me of the way you described the resilience of growing up in a mining community. It’s not that feeling that every time something goes wrong, it’s like,”Oh, no!” It’s more of an understanding that life will have challenges and even though it’s hard sometimes, it’s another opportunity to keep moving forward, keep learning, move into the next layer.

Linda: Yes.

Erin: I also think that our society, and maybe many others as well, categorize work as a negative thing. It’s seen as something to be avoided, but when work has either purpose or enjoyment for us, it can feel like a very positive thing. I also think it’s interesting that work is kind of compartmentalized as a whole separate entity. Sometimes aspects of life actually just all kind of weave together so that we can really be energized by something, even if it requires quite a bit of our effort.

I’ve noticed that you’ve always been very keen to share you experience and ideas with other families who might be in various stages of imagining things for their sons or daughters. It is one more thing to do though. Does the idea of being energized by something even though it requires effort resonate with you? If so, what is it about sharing with other families that is energizing?

Linda: So, around the idea of work, if you think about people working at some of the organizations you and I are familiar with, the people there – what they do is “work.”

Erin: Yes, in a technical sense. Like even if they enjoy it, they are paid to be there for a certain number of hours.

Linda: Now, I, or other families, might do many of the same things that they’re doing, sharing with families and offering ideas in different ways. Some people might refer to some of the things you were just talking about as work, yes, but I never thought about it as work. I did think about it as being very energizing. I’m a person who needs to be energized by an idea or what needs to be done… like I don’t have endless natural energy. I love to write and I love to speak, like public speaking. I don’t consider myself a public speaker or writer per se, but I like being involved in that.

Very often if I am talking to parents and they say, “How were you able to do all of this? It sounds like a lot of work.” And my answer would be that it’s very energizing. If you are part of trying to make something happen, maybe not everything you want to happen does, but you have a framework and inside of that, there are things you are working toward. If one of those things works out, that that energizes you to move forward to the next thing. I think it requires lots of thought and reflection, so if you’re not inclined to want to spend time thinking and reflecting, then I don’t think it will be … I think that’s all part of it. I think a lot of people want things to be taken care of. Like they want the government to do something about different things. I’d like the government to do something about certain things too sometimes, but I know you have to work toward that. You can’t just expect it.

I think it is very energizing to learn and work toward things. I think for all people, if there’s something that needs to happen in life and even a bit of good comes from your efforts, you’re motivated to go further.

Erin: Oh yes, it builds momentum.

Linda: I guess too that the work I’ve done as adult in nursing in critical care, you’re in that situation of things not always working out, but also of very significant things working out. You know if a patient codes and the medical efforts are successful, that’s energizing. If you’re in a situation where nothing is working out, it’s not energizing. It’s depressing.

It’s a complicated thing but it’s a realization or recognition that you really put some focus into something and there’s kind of a basic framework that gives you guidance, but if you’re not open to that and it’s an expectation that someone else with energy or focus is going to do that for you then …

Erin: Yeah, I think I know what you mean. There can be a sort of complacency that people have that things will get done by an outside source – often they name the government – and sometimes they do, but when we see people moving forward with their own motivation or we begin to do that, we realize that we can choose to move ahead ourselves or in collaboration with others with things we’re interested in or have a need for.

Linda: The other aspect to all of this, and maybe life in general, is just the idea of the people that you have around you. I think about this with some of my regular phone calls – I can just be feeling overwhelmed and down in the dumps and not knowing what to do next and then the phone rings and I’m asked, “Hi Linda, how are you?” and I answer, “Oh, fine,” and then I have a good chat and at the end, I think, “Well, now I feel better.” But that’s true in all realms of life. But it’s just that connection itself; it’s not even so much what happens within that. In the old days, it was the neighbour across the street and you knew that if you knock on the door, you’d likely have a visit, and get invited in for a homemade root beer or whatever.

Erin: Right, right. We find those things … well, sometimes they find us, but they give us a shift. They shift our focus. It’s a good point because I think when we think about self-directed learning or living, the word “self” might make it seem like it has to be alone, but really it can involve connecting with maybe even many people. It’s just the idea of exploring or moving ahead with something that is really coming from within, rather than being imposed. But yeah, it can be so helpful to recharge with other people as well as we go along.

Linda: Right.

Erin: Linda, I have another question here. Sometimes we get introduced to different things through people and then they end up enriching our own life. Maybe those things become a sort of springboard into new interests for ourselves. I know you’ve learned a lot of interesting things from Tiffany and the different gifts and interests she has had in her life. Can you talk a bit about those?

Linda: Oh, yes. I often wonder if it wasn’t for Tiffany what I would and wouldn’t have experienced. Certainly there’s a whole pile of people that I wouldn’t have known. And I think because the thing Tiffany’s loves most in life is people and socializing and hosting and what not. She remembers people so well. You know people will say to me that they haven’t seen Tiffany maybe for many years and do I think she’ll remember them. Well, Tiffany remembers everybody. Her response really shows people that, I think, and that they’re appreciated and welcomed. I guess because of some of that, I’ve had the opportunity to meet a whole lot of people. And of course each of those people has their own interesting things, so it sort of grows and grows.

I wonder how open I would be to people if I didn’t have Tiffany as a role model. I really don’t actually consider myself to be social person. Sometimes I don’t really like being with people all that much, lol, but I do want to be responsive to them. I often think though that I’m not as appreciative of them or as responsive as I could be … it’s hard to explain.

Erin: Yeah, no, I think it makes sense to me. I think it might actually be quite common of reflective people. They are interested in people, they care about people, but they don’t necessarily want to be in people’s presence or having conversation all the time. It’s likely related to introversion and extroversion and all of that as well, but that’s another conversation, lol.

Linda: Yes, and I find often people tell me their stories. I don’t necessarily ask them their stories, but when they are telling them to me I find them very interesting. I’m not good at delving into people’s – like it’s not wanting to be intrusive. Maybe that comes back from my childhood of getting into trouble for asking questions, but yeah, it is interesting when people just naturally tell stories.

So, the other thing I think from Tiffany is that I think she’s really, really intuitive and I think she brings out the best in people, given the opportunity for people to be in her company and get to know her. You know, I think that she provides opportunities for people to think about things differently just by being in her company.

When Tiffany was a baby, she and I were visiting Nova Scotia and we were sitting beside the window. She kept looking out at this big, beautiful tree so intently. It may have been an oak tree. She was noticing everything in the tree … the birds that were singing, the leaves, the way the branches were swaying. She just kept turning her head and looking and looking and it made me slow down a bit. I had seen that tree so many times but I was drawn in by her curiosity and it made me more observant as well. She continued being interested in nature, enjoying the outdoors and examining all the details. So that is something else I have learned from her. Through her broad scope, she has provided a lot of learning to me.

Erin: Oh absolutely. And some other things come to mind as well. So for me, I have learned so much from things I’ve been introduced to by Tiffany. It’s expanded my thinking as far as different kinds of music and art. So, even beyond her own art or drumming, because she’s interested in cultural places and music and events and galleries, I’ve been introduced to lots of different aspects that I take an interest in finding out more about. She’s offered a real window into lots of things.

Linda: Yes, her art and music have been such a significant part of her life and they have definitely influenced those around her. I’ve always thought that Tiffany’s love of music and art and particular environments have also been a product of the people she loves being with. I guess it goes both ways. When you enjoy something, you’re naturally drawn to people who enjoy those things as well. In our family, we’ve always been very musical. Some people sing well and some play instruments and there is an interest in music that is partly that and partly the social aspect. Her art as well has seemed like a passion she loves to share with a friend who she cares very deeply for.

She loves the pomp and ceremony of the Catholic Church. It involves music and art and lots of people so a lot of it connects.

I think this might be true of all people. You think about the things that you are interested in or might be passionate about and often it might circle back to people. If you hadn’t had those relationships or met those people, would those have remained undiscovered? Maybe not in all cases …maybe lots of people that are interested in art and music and those sorts of things might be introverted people, I don’t know…

Erin: Yes, but even then, people are often influenced by someone they read about, or see on TV or hear on the radio or conversations with people. Ideas and introductions to things and deepening of those are definitely passed on from person to person, whether that’s in real life relationship or someone whose work they read or whatever …

Linda: But yes, her involvement in those things helps other people appreciate them even more.

Erin: We develop other aspects of ourselves as a result of those first things we learned from somebody and then that transfers to other people. We broaden our knowledge and curiosity and then others do too … yeah, it’s amazing actually.

Linda: Yes, when you talk about these things in relation to a person with a disability, the answer, like so many other things, is just really the same as how all people do things – it’s the same process in a lot of ways. It’s whatever people have in their heads and hearts that directs them to where they go.

Erin: Right, right. I love that. It’s what we all do, how we all live and learn.

Linda: Yes, right.

Erin: Linda, you’ve done a lot of learning and sharing with other people but I know you to be a curious person in general. What kinds of things have you been interested in just for yourself over the years? What things are you interested in most recently?

Linda: Oh, do I get to answer this question over several days, because it keeps changing, lol?

Erin: Sure. This won’t be going out for several days so that’ll work!

Linda: Today I’m interested in this, tomorrow, I don’t know, lol. Well, one of things I’m always interested in is what is going on in the world. Nowadays I’m struggling with the news because I feel so much of it is all the same, just restated or whatever. I don’t believe it’s all the same. I just believe that certain things are being focused on in certain parts of the world. So, it’s hard to find out what’s happening in other parts of the world. There’s no real way of knowing. There must be other things happening, but it’s hard to get access to them. I wonder what’s happening in Syria or any other places. I don’t always hear much of those anymore. But yes, I’m very interested in what’s generally happening in the world.

I’m interested in seeing coverage of cultural celebrations – some things like that as well – different religious things. I find that fascinating. I’m curious about the differences but also commonalities in different faiths and cultures. I’ve just always been interested in learning more about that.

Erin: Which is interesting because it all kind of ties back to your curiosity over the years about things that divide people, but then also the “why” and what leads to connecting people instead.

Linda: Well, yes. Yes. As for other interests, I’m very interested in writing. I have written a good portion of a book about Tiffany’s life. I like to put words together and in that process, things come to me. The process of writing can be a learning experience. Other things come to mind and then I find out more about them.

I’m interested in reading. I like to read lots of different things but I’m not able to do that so much anymore. I guess I just like knowing about things. I like knowing people’s opinions. I don’t always agree with them but I hardly ever argue with people about them. I’m interested in music and a variety of music, although maybe not as much as I use to be.

I’m interested in helping people in natural ways. I don’t think I’m someone who is driven to help just for the sake of it. I don’t go around looking for people to help, but I am interested in people’s well-being. I do think about how people are feeling and doing and as things come my way, I’m interested in doing those things.

Erin: Hmm-mm. I’ve always thought of you as being interested in community and I don’t think that has to be … well, it’s different for everybody. Like I don’t think it needs to mean knocking on people’s doors. For me, I’m probably not going to be a neighbour who knocks on the door with cookies, but I do try to be available and friendly and kind of just keep an eye out. I think there are different ways of being interested in community.

Linda: Yeah, yeah.

Erin: I think we’ve come to the end of our questions! Linda, thank you so much for the time you’ve given to chat this through with me.

Linda: Oh, you’re welcome. I hope you can make some sense of it all.

Erin: Oh yes, it was exciting today to learn even more actually… pieces I hadn’t realized at all.

There is something here that I’d like to leave with …

You were interviewed by Genia Stephen from Good Things in Life podcast and I really enjoyed the conversation you had with her. Your final words in that interview were really encouraging to me. I think you’d been asked what advice you would give to parents of young children with intellectual disabilities. I have chatted back and forth with parents over time, whether they have children with exceptional needs or not, and I was so struck that those words have a lot of wisdom for all of us, all children and all adults.

Here is a slightly paraphrased version of those words you shared:

“I would just say to be very, very open to what the possibilities could be for your son or daughter and listen. Just listen very carefully to them and not kind of fall into that trap of someone saying that your child wouldn’t be capable of this or that other thing. Because I don’t think that any of us really knows that about ourselves even without having the opportunity, to a certain degree, to explore that. We can’t, you know, we can’t do everything, we can’t make everything happen that we’d like to have happen.

But I think that we just have to listen and observe and invite, invite other people to help us and take advantage of those opportunities. Not limit ourselves. And I think if we don’t limit ourselves then we probably won’t limit our children. Having said all that, there are limits in life. But we just have to try. And I think parents generally end up doing the best that they can do. I think because of this world we live in and the world that we probably always will live in, there will always be limitations that are placed on our children, but that we can do all that we can to work around those or find other ways. So yeah, it’s all worthwhile. It’s very worthwhile.” – Linda Dawe

Enjoy this post? Please share.

I enjoyed this interview very much! So many of the things Linda said and the ideas she expressed resonated deeply with with me but also gave me pause to reflect on things that I think I hadn’t considered. Thanks you Linda, for, your wisdom and insight.

Such an interesting interview, thanks Erin and to Linda for sharing her stories. I love the thread running through about connection enriching our lives and shifting our focus. Linda reflecting on how much she’s learnt from her daughter, Tiffany – what wonderful insights and so relatable. That joy-filled photo. And the end quote …if we don’t limit ourselves then we probably won’t limit our children… Powerful 🙂

I agree, Hayley. I loved the end quote – there’s lots of wisdom in those words! I will pass your lovely message on to Linda. Thank you so much for your comment:).

This is so, so interesting. The quote at the end is useful for us all. Wow. “it’s all very worthwhile.” Oh yes. Thank you very much for sharing all of those stories🌸.

Glad you enjoyed it, Allie. Thank you!